Diabetes was first recognised as a medical condition over 3,000 years ago, the ancient Greeks coining the term Ziabites. Many ancient civilisations including Egyptian, Indian, Chinese, Persian and Arabic, offer descriptions of diabetes and herbal treatments. The metformin story itself can be traced back at least 400 years from western herbal medicine to the present. This is my attempt to distil the vast amounts of information available into something for anyone to read. There are academic references for those who might want to read more about the journey from herbal medicine to Metformin now being on the World Health Organisation (WHO) list of essential medicines and is the most widely prescribed drug for the treatment of Type 2 Diabetes (T2D). It has also been recognised for having beneficial effects on the cardiovascular system, gut microbiota, wound healing and aging. Other possible uses for metformin that are being explored include cancer and motor neurone disease. This has led to it being identified as a potential wonder drug in several respected scientific journals (e.g. Matz and Zhou, 2023; Schmerling 2024). So how did we get from a herbal remedy to where we are with metformin?

Herbal beginnings

The plant Galega officinalis, more commonly known as goat’s rue or French lilac, gets a mention in Culpepper’s Complete Herbal of 1653. However, this was for the treatment of worms, fever and epilepsy rather than diabetes. About the same time, the famous English physician, Thomas Wills, described the symptoms of diabetes, including thirst, frequent urination and the sweetness of the urine. Tasting urine was common practice in ancient medicine but probably not something clinicians would be happy to contemplate today. The mellitus in diabetes mellitus comes from the latin word for honeyed or sweet tasting!. In 1772, John Hill, described the use of Galega to treat thirst and frequent urination. In the mid 1800s chemists found that Galega was rich in guanidines marking the start of the development of metformin itself.

From herbs to chemistry

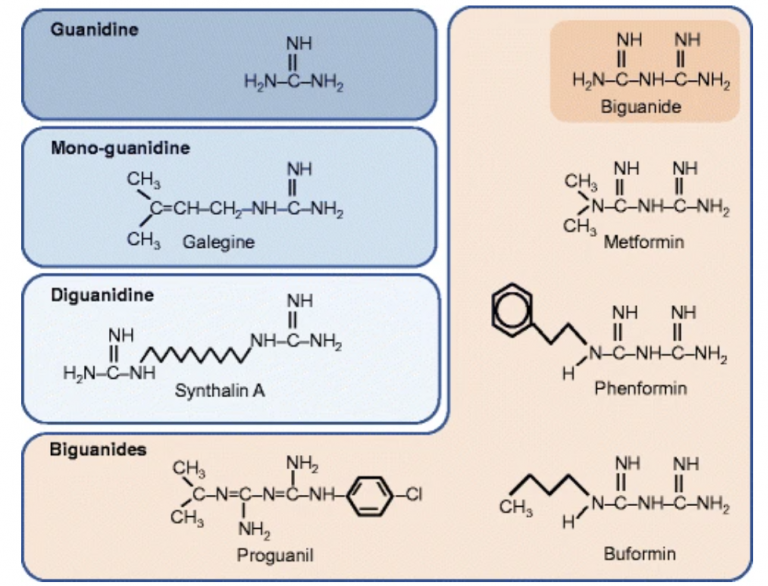

In 1918 guanidine was noted to lower blood sugar levels in animal studies, kick starting attempts to synthesise a range of guanidines with the aim of controlling blood dugar levels. In 1920, two such compounds, called galegine and synthalin (see figure 1 below) were synthesised and tested. Whilst showing the desired effect of lowering blood sugar levels, both were very toxic, making them unsuitable for consideration as drug candidates.

In 1922 Werner and Bell successfully synthesised metformin (dimethyl biguanide) but it wasn’t until 1929 that metformin, along with other biguanides, were tested for blood glucose lowering activity in animals. Whilst bloog glucose lowering effects were seen, because only normal animals were used, very high doses had to be given to achieve a significant effect. It was noted however that the biguanides, particularly metformin, were not as toxic as previously tested guanidines. However, because of the very high doses required there was no attempt to further develop metformin as a therapy at this time.

Defining studies

In 1956 the physician Jean Sterne and his pharmacist colleague, Denise Duval, were working for Aron Labs, near Paris in France. Sterne was aware of the previous work on biguanides and conceived the idea of revisiting the animal studies but using both normal and diabetic animals. Metformin was finally shown to be effective, with low toxicity, at acceptable dose levels. In 1957 Aron Labs marketed metformin under the brand name Glucophage (literally glucose eater).

The competition

Around the same time however, labs in Germany and the USA were reporting success with the related compounds phenformin and buformin. Phenformin gained popularity in the US, whereas buformin was more popular in Europe. In the late 1950 safety testing was much less rigorous than it is today. Thalidomide, probably the most infamous of drugs, was first marketed in 1958, and its effects changed the way drug were regulated subsequently. Both phenformin and buformin were withdrawn from sale in 1970 due to toxic side effects, in particular lactic acidosis, in which the blood becomes too acidic with potentially lethal consequences.

US approval of metformin

In the early 1980s, Aron Labs were acquired by Lipha Pharmaceuticals. Lipha asked the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The FDA asked for a lot more data on the safety and efficacy of metformin, triggering several clinical trials. FDA approval for metformin was finally given in 1994, over 25 years after it was first marketed in Europe.

Other beneficial effects of metformin

The late 1990s saw the publication of several reports arising from the UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS). The UKPDS was set up in the late 1970s, by Dr Robert Turner and colleagues in Oxford and ran from 1977 to 1997. 5102 subjects at 23 centres across the UK took part in the study. which examined a number of diabetes treatments, including metformin. A key finding was that long term therapy with metformin reduces cardiovascular risk, i.e patients taking metformin were less likely to have heart attacks and strokes (see King et al 1999 for a trial overview). A subsequent 10 year follow up study confirmed these findings (Holman et al 2008).

More recent studies have also found beneficial effects on gut microbiota and wound healing alongside reduced cancer incidence, anti-aging effects and in the treatment of polycystic ovary syndome. Ongoing research is also looking at potential beneficial effects in cancer treatment, motor neurone disease and a range of other conditions (see Chaudhary and Kulkarni 2024; Petrie 2024, Sulong et al 2025).

Clearly metformin is more than just a glucose lowering agent, but how does it work? There are a lot of studies ongoing into understanding the molecular effects of metformin. These have shown that metformin increases insulin sensitivity; decreases glucose absorption the gut and its production in the liver; inhibits mitochondrial complex 1 and affects DNA methylation patterns.

The down side

Like all drugs it does have its side effects and I’ve mentioned my own experience of some of these in previous posts. Spookily as I started writing writing this post yesterday, 15 December 2025, there were stories in the UK press about NHS warnings concerning serious side effects from metformin. I’ve no idea what triggered these warnings but here’s some detail and my thoughts.

A serious side effect is defined as affecting less than one in 10,000 people. The ones highlighted in the press were

- a general feeling of being unwell with severe tiredness, fast or shallow breathing, being cold and a slow heartbeat

- the whites of your eyes turn yellow, or your skin turns yellow, although this may be less obvious on brown or black skin – this can be a sign of liver problems.

For these the NHS advises calling your doctor or 111 – good luck with either of those. Call handlers on 111 will probably tell you to go to the emergency department at your local hospital.

Also highlighted is serious allergic reaction (anaphylaxis). The NHS advice is to call 999 now if:

- your lips, mouth, throat or tongue suddenly become swollen

- you’re breathing very fast or struggling to breathe (you may become very wheezy or feel like you’re choking or gasping for air)

- your throat feels tight or you’re struggling to swallow

- your skin, tongue or lips turn blue, grey or pale (if you have black or brown skin, this may be easier to see on the palms of your hands or soles of your feet)

- you suddenly become very confused, drowsy or dizzy

- someone faints and cannot be woken up

- a child is limp, floppy or not responding like they normally do (their head may fall to the side, backwards or forwards, or they may find it difficult to lift their head or focus on your face)

Signs of a serious allergic reaction can also include having a rash that is swollen, raised itchy, blistered or peeling.

There doesn’t appear to be anything new in this information. Every pack of metformin contains a patient information leaflet with these (and other side effects) detailed. Not that many people bother to read the patient information leaflets! Serious side effects are pretty obvious so common sense should tell you to take action without this kind of press attention. Potentially this could put people off taking their metformin medication, even if they don’t have these serious side effects. Yes, we all need to be aware that there are always side effects with every medication. There is always a balance to be struck between the benefits and the bad stuff. In the case of metformin, I’m happy to keep taking it, but everyone needs to make their own mind up based on evidence not scare stories!

References

Bailey, C.J. (2017) Metformin: historical overview. Diabetologia 60, 1566–1576. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-017-4318-z

Chaudhary, S., Kulkarni, A. (2024) Metformin: Past, Present, and Future. Curr Diab Rep 24, 119–130 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-024-01539-1

Holman RR, Paul SK, Bethel MA, Matthews DR, Neil HA. (2008)10-year follow-up of intensive glucose control in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med.;359(15):1577-89. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0806470. Epub 2008 Sep 10. PMID: 18784090.

Karamanou M, Protogerou A, Tsoucalas G, Androutsos G, Poulakou-Rebelakou E. (2016) Milestones in the history of diabetes mellitus: The main contributors. World J Diabetes.;7(1):1-7. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v7.i1.1. PMID: 26788261; PMCID: PMC4707300.

King P, Peacock I, Donnelly R.(1999) The UK prospective diabetes study (UKPDS): clinical and therapeutic implications for type 2 diabetes. Br J Clin Pharmacol.;48(5):643-8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00092.x. PMID: 10594464; PMCID: PMC2014359.

Matz AJ, Zhou B. (2023) A wonder drug? new discoveries potentiate new therapeutic potentials of metformin. Obes Med. 2023 Oct;43:100514. doi: 10.1016/j.obmed.2023.100514. Epub 2023 Oct 6. PMID: 40761706; PMCID: PMC12320519.

Petrie JR. (2024)Metformin beyond type 2 diabetes: Emerging and potential new indications. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2024; 26(Suppl. 3): 31-41. doi:10.1111/dom.15756

Schmerling (2024), https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/is-metformin-a-wonder-drug-202109222605 (accessed 15/12/2025).

Sulong, N.A., Lee, V.S., Fei, C.C. et al. Exploring multifaceted roles of metformin in therapeutic applications, mechanistic insights, and innovations in drug delivery systems across biological contexts: a systematic review. Drug Deliv. and Transl. Res. 15, 4043–4066 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13346-025-01903-y